Future: Rotterdam as national park

The National Park Rotterdam exhibition at the Natural History Museum Rotterdam will hopefully get you excited about nature in the city and encourage you to explore further opportunities for nature in the city in the future. A diverse group of designers, developers, ecologists and experts from Heijmans, Witteveen+Bos and Bureau Stadsnatuur have tried to articulate and represent this idea of the city as a national park. We used various websites, publications, media and insights. Here, we will share some of these sources of inspiration.

Symbiosis: people and nature together in the city

Living, working, travelling and building in Rotterdam’s future as a national park. The intensive interaction between people, the built environment and nature is characteristic of the city. By regarding green and nature as fully-fledged partners in the future1, we can attain or bring back many qualities to the city2. This requires seeing the city as an (eco)system in which we are a cog in the wheel and pay attention to what is needed, instead of bending everything to our will out of self-interest3. By now, we have learned that this attitude has led to one crisis after another. Biologists call a mutually beneficial collaboration a symbiosis. Will the period to come then be the Symbiocene4? We have been dreaming about the future and imagining what it might look like. Please share your own dreams and thoughts with us.

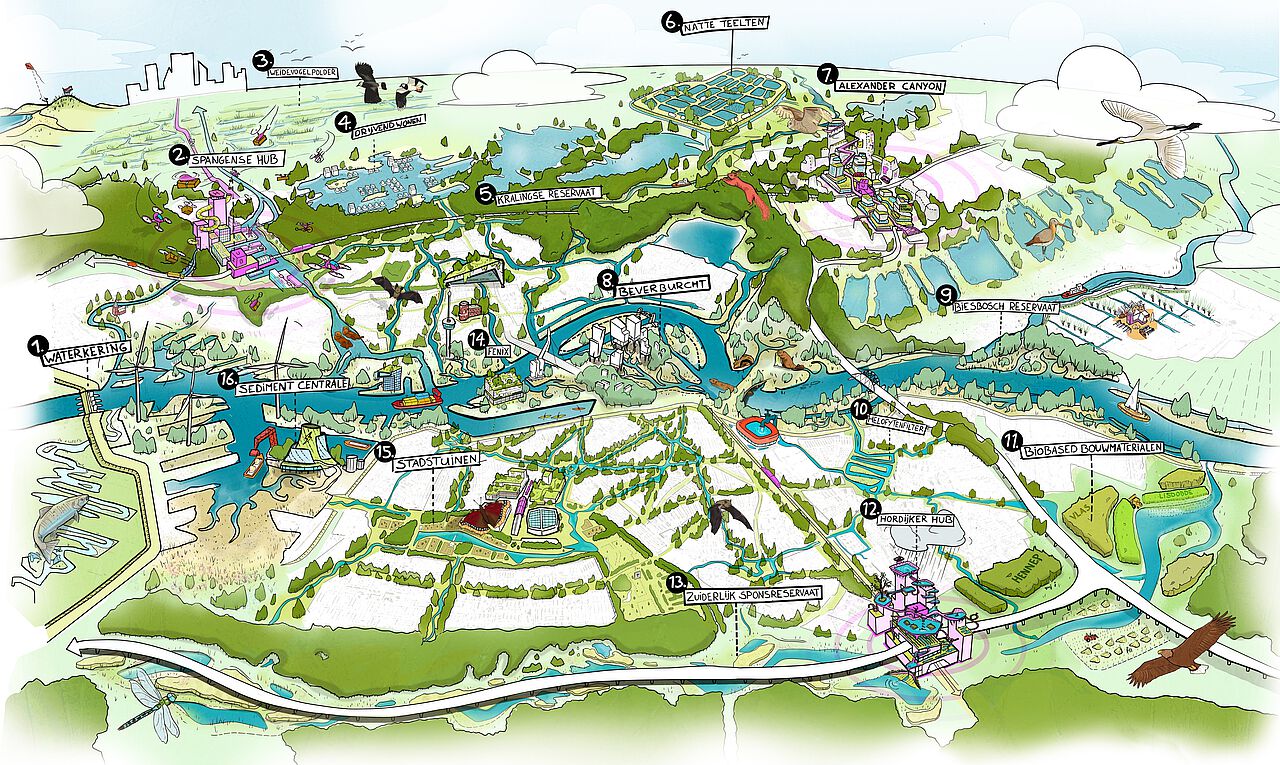

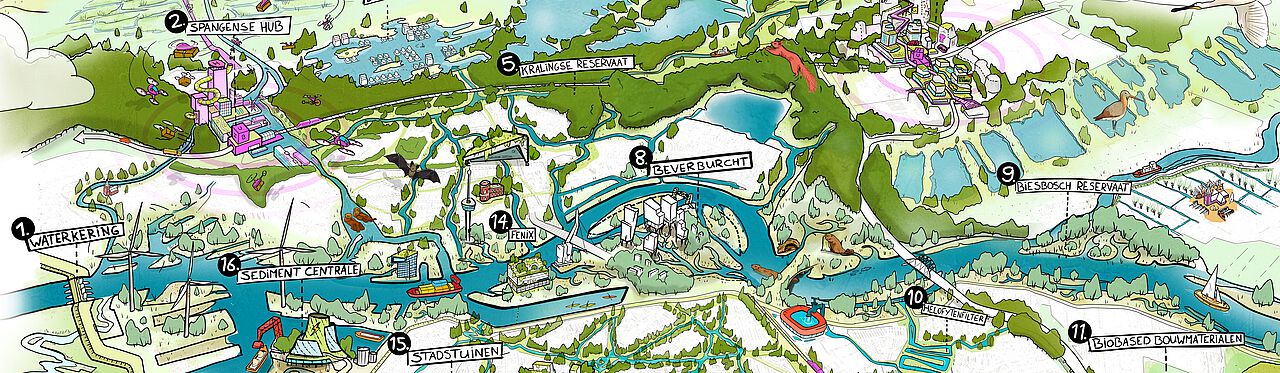

Bird’s eye view - Rotterdam as a national park

The future map in the exhibition shows lush nature in the city, with Rotterdam-South in the foreground. In the drawing, several nature-rich spots and connections stand out that are good for people and nature. It greatly enhances the city’s liveability: nature provides cooling, enjoyment, biodiversity, health and well-being.

Reserves, green arteries and ecological hotspots

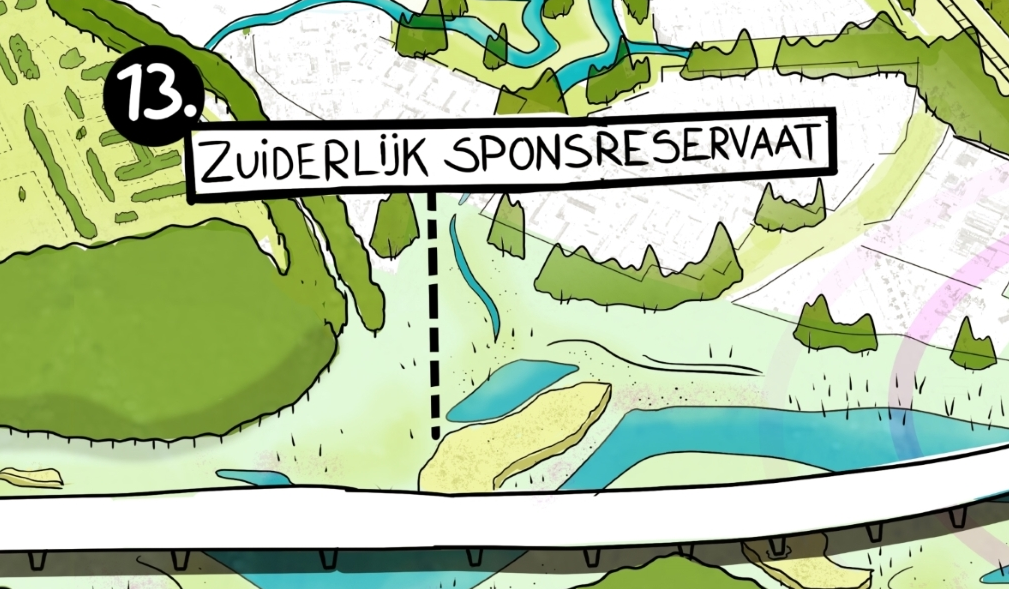

- Urban reserves are large natural areas with natural dynamics and without too much human disturbance: woodland in the Kralingse Reserve (5), riverside nature in the Biesbosch Reserve (9) and marshland in the Southern Sponge Reserve (13). These core areas are important anchors for robust biodiversity, to act as cooling batteries for the city, capture CO2, filter the air and store water during peaks in rainfall. They are also attractive for recreation and relaxation, together with family and friends or by yourself with a book under a tree.

- Green arteries of the city are the ecological network connecting all reserves. Avenues and canals become green routes and water connections, where people and animals live and travel together. You can see this in the map, for instance, in the pre-war canal structures and green boulevards where there are now through-traffic routes. In the future, these green corridors will be great for walking and cycling, allowing us to move through the city healthily and without pollution.

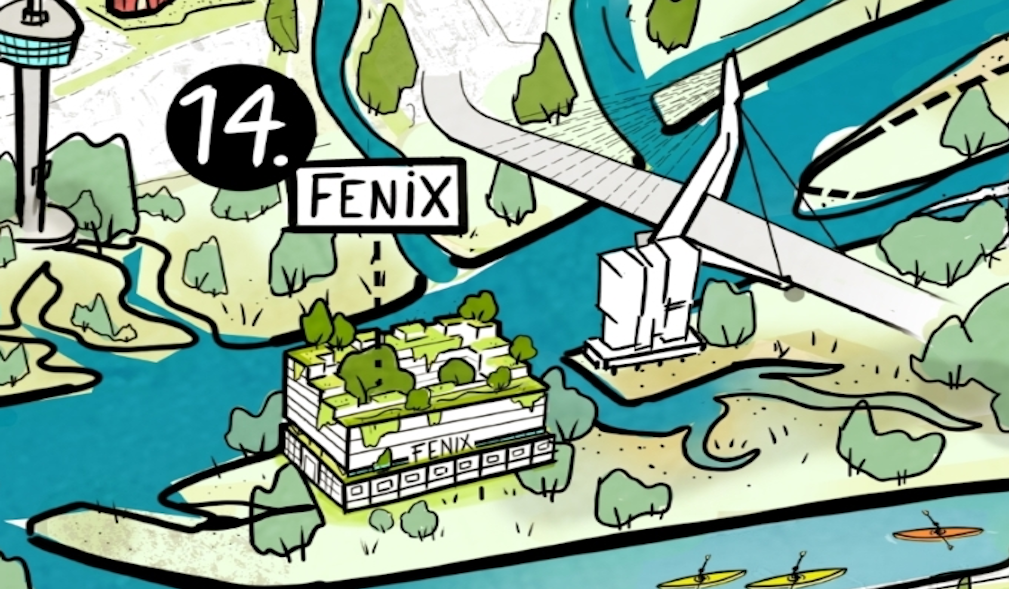

- Green hotspots in the city are the ecological stepping stones of the network. These are places rich in biodiversity, such as green buildings with plants growing up against and on facades and on top of roofs. Roofs with water collection, for instance, are a huge help in the challenges related to heat and water. The image shows several iconic buildings that could be such a location, such as Ahoy, the Fenix Warehouse (14), ‘Alexander Canyon’ (7), and the Kop van Feijenoord as a ‘Beaver Lodge’ (8), since the Biesbosch is also connected to Rotterdam. The more functions these places have, the more attractive they are for flora and fauna. In the large hubs (2, 7, 12), every square metre is used for various functions and thus optimally used5. Consider, for instance, transport, distribution centres, work studios and water collection.

Biodiversitity

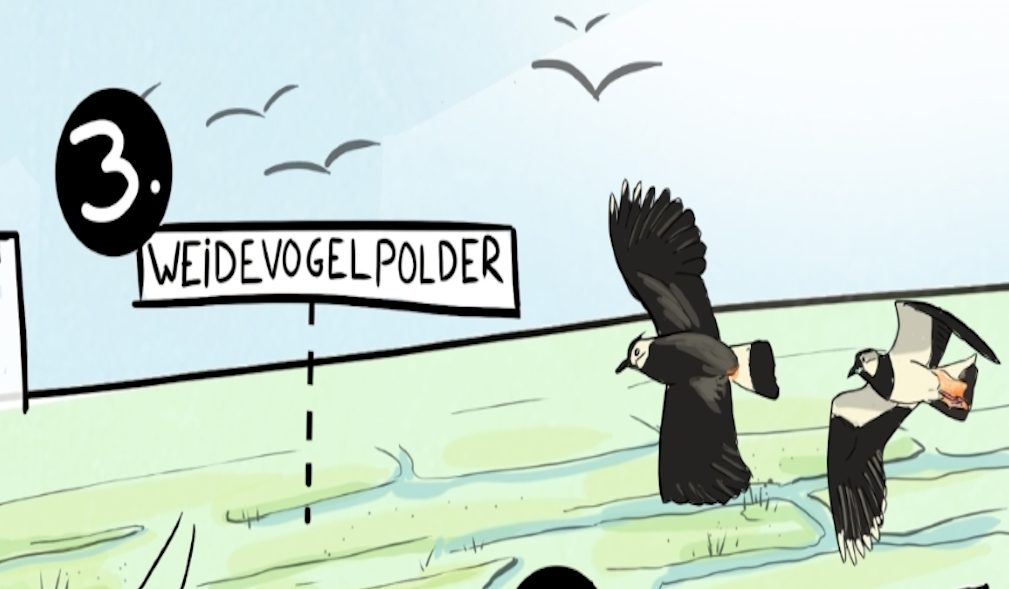

This network of reserves, corridors and green hotspots offers plenty of places for nature to feel at home and move along6. The trees, shrubs and herbs match Rotterdam’s soil and groundwater, so biodiversity is high. The different heights and types of greenery, and the careful handling of soil life and water quality strengthen the system, resulting in a resilient nature that can withstand storms and setbacks7. Butterflies, birds, bats and other mammals, all these animals have a place in the city and even the squirrel is returning! Along the Meuse, robust marshland nature has a place again, with beaver dams and white-tailed eagle nests. Areas around the city will also have space for nature, such as in the Meadow Bird Polder (3).

It is precisely by increasing biodiversity that useful species will be sufficiently present to be of significance. Thus, potential pest species can be limited with natural enemies, without further human intervention. Small plants and animals like algae and mosses store CO2 and capture particulate matter. In the green city, pollinators such as wild bees are also abundant, which help produce our food locally with food crops in vegetable gardens, food forests and on rooftop terraces.

Layout of the city

The fact that our current use of space is being shaken up is insurmountable, but we also get a lot in return. Traffic and parking make way for greenery and water. Cycling, walking, good public transport and local production and consumption make for radically different city logistics. Supply takes place through large multifunctional hubs at strategic locations on Rotterdam’s ring road, where residents pick up goods or where small, modern vehicles transport goods into the city. In Alexander Canyon (7), for instance, food and goods are not only consumed but also produced. The architecture is a human-made rock formation, which is attractive to various animals. The supply route of food and building materials produced around the city also runs along the big urban hubs (2, 7, 12). Areas around the city will have space for wet cultivation of crops such as red rice (6).

The Flood Defence (1) is needed to keep salt water in the sea and create more room for river water. Sea levels will have risen in the future due to climate change. If the salt sea water rises too much, it pushes up the rivers and partly replaces the fresh water, including in the hinterland8. This not only prevents the river from discharging its water properly, it also means that the hinterland will partly become saline. This will cause trees to die, pastures to become unusable and some animals will no longer be able to live in or around the river. Where sea and river meet at the Flood Defence, we can exploit the opportunity to generate electricity from the ion exchange between fresh and salt water 9. Tides also provide opportunities for energy generation, as does wind power.

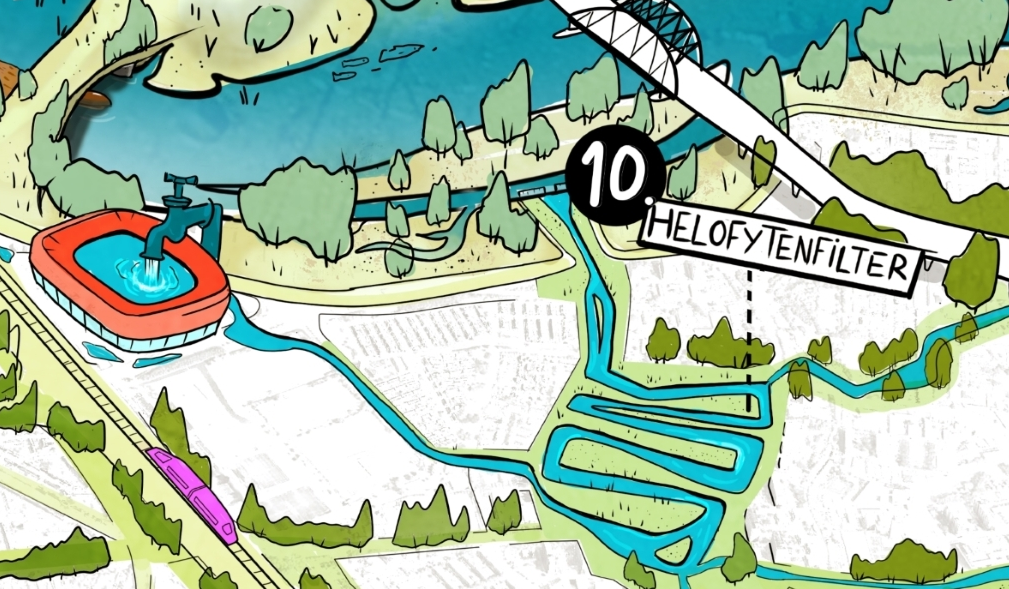

Rainfall must not lead to flooding, so we will need to be able to store the load of rain locally and around the city like a sponge. This requires space, but these places can of course be used for other purposes as well, such as recreation in the Southern Sponge Reserve (13). We need the collected water to produce drinking water, as it will be scarce due to precipitation shortages. With natural filters (helophyte filters10) we can already purify it to a large extent, such as at Brienenoord Island (10) and the Kuip as a ‘bathtub’, as well as allowing typical river Meuse nature to develop. In this way, we can create local drinking water supplies and also have sufficient water for drier periods.

Cycle

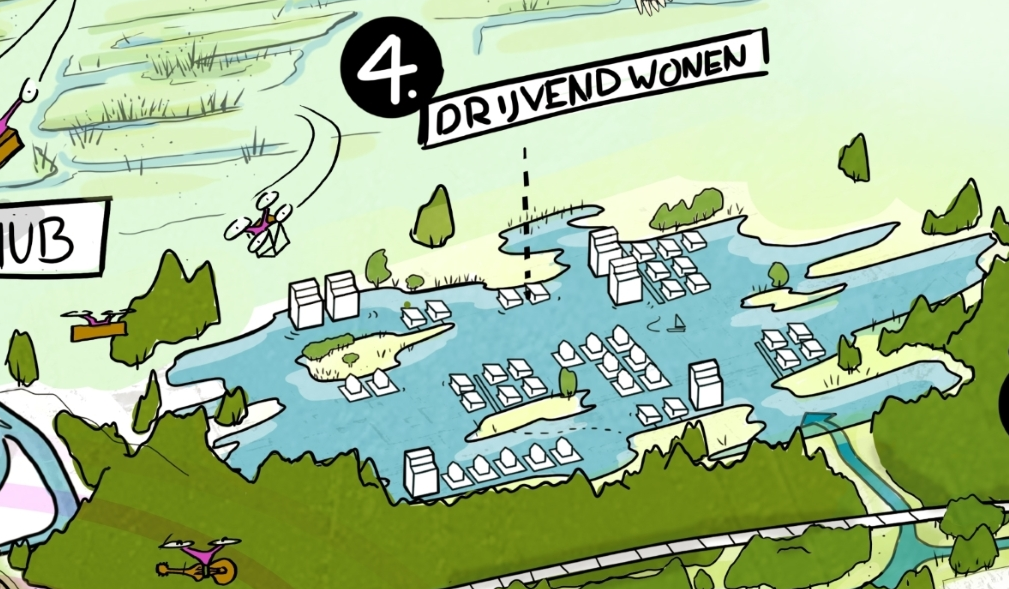

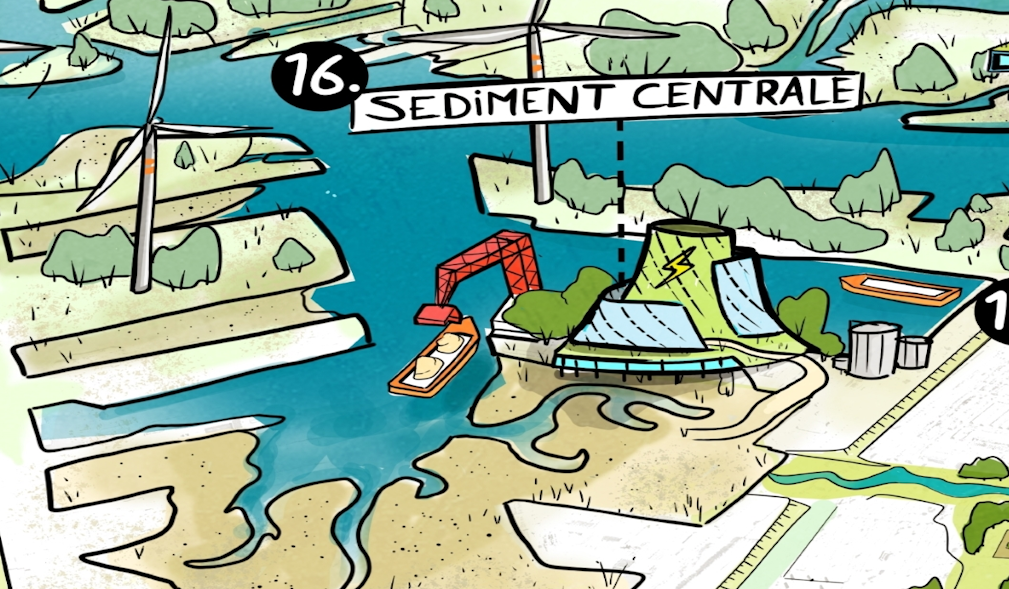

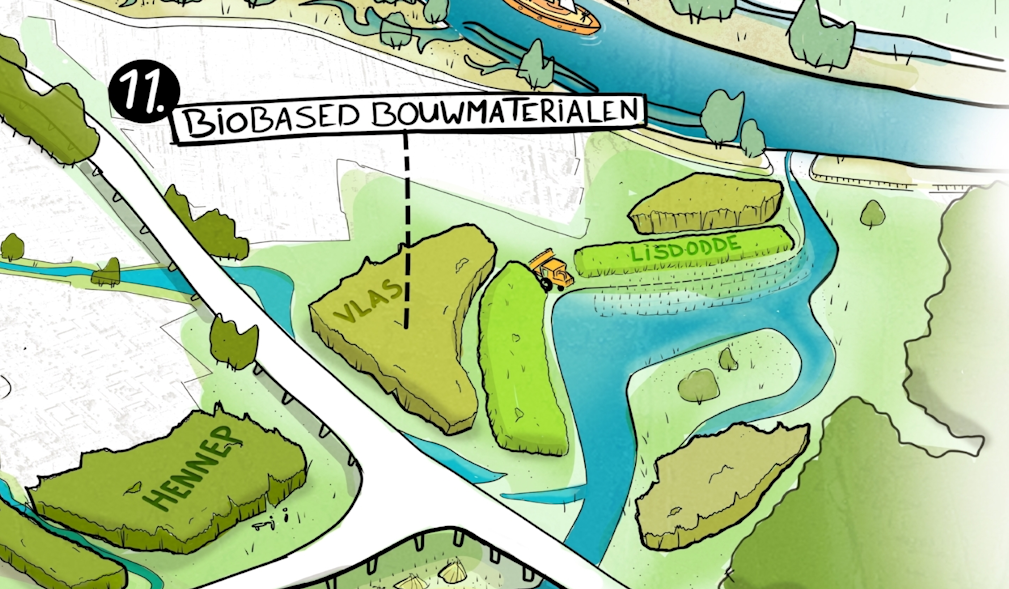

As we spend more time recreating and working locally while also using products from the region, Rotterdam-The Hague Airport will be transformed into a robust water storage facility with floating homes (4). This is how we combine uses in a long-term sustainable way. We no longer source raw materials from far away. Close to home, we harvest and find many useful and sustainable materials. The river carries sediment to the Sediment Centre (16), where materials such as sand, clay and pebbles are extracted, which can be used as building materials. Wood and crops like flax, fibre hemp and bulrush are renewable, of natural origin (also called biobased) and can grow just fine in cities and along the banks of the Meuse (11). For instance, wood can be used as construction timber, and flax, fibre hemp and bulrush are fine insulation products. As these raw materials grow, they are part of nature. They provide a home for animals, help keep the city cool, provide a setting for recreation and, of course, store CO2.

Sources

[1] Een natuurlijkere toekomst voor Nederland in 2120, rapport Universiteit Wageningen

[2] Marian Stuiver (2023) De Symbiotische Stad: Een enkeltje Natuur Centraal in urbane transformaties. Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen.

[3] Growing dwellings | TU Delft Repositories

[4] welkom in het Symbioceen - VPRO

[5] van den Brink, L., Rooij, R., Tillie, N. (2022). In-Between Nature: Reconsidering Design Practices for Territories In-Between from a Social-Ecological Perspective. In: Roggema, R. (eds) Design for Regenerative Cities and Landscapes. Contemporary Urban Design Thinking. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97023-9_7

[6] Rewild My Street | Greening City Streets for Wildlife

[7] Home - London National Park City

[8] Haasnoot, M, F. Diermanse, J. Kwadijk, R. de Winter, G. Winter, 2019, Strategieën voor adaptatie aan hoge en versnelde zeespiegelstijging. Een verkenning. Deltares rapport 11203724-004

[9] Door een membraam tussen het zoete en het zoute water kan energie opgewekt worden. Dit heet Blue Energie en is door het Nederlandse REDstack ontwikkelt, die uniek is in de wereld, samen met moederbedrijf Wetsus en Fujifilm.

[10] Planten als waterzuiveraars: helofytenfilters | Green Cities (thegreencities.eu)